I am enraptured by Itō Jakuchū’s art. The stark contrast between the ink-black background and the bold use of color on the foreground is immediately striking, sure. But it’s more than that.

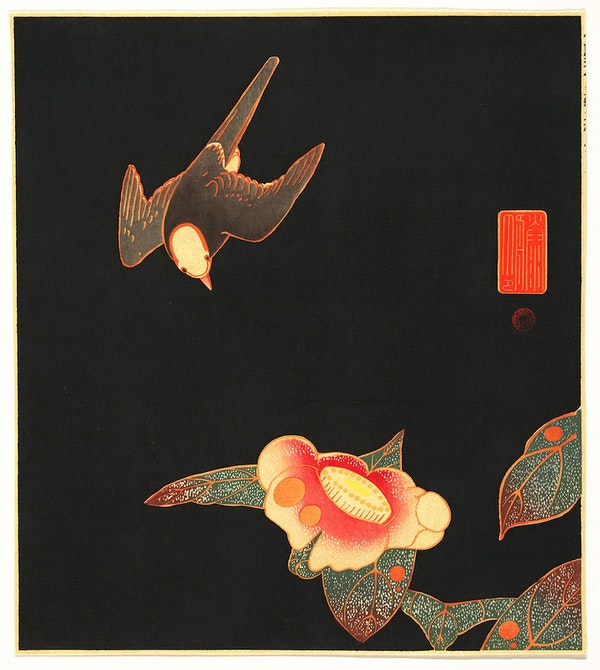

The hues on Swallow and Camellia are not jump-at-you bright, but they are made dazzling nonetheless by graceful saturation. The crimson on the camelia is both soft and intense. Earthy tones on the leaves capture a natural elegance that reminds me of furyu (known in Chinese as fengliu) — a sense of sophisticated beauty present in nature. The concept of furyu originated in the Heian period and often translated to dazzling gardens inspired by a mindful appreciation for nature.

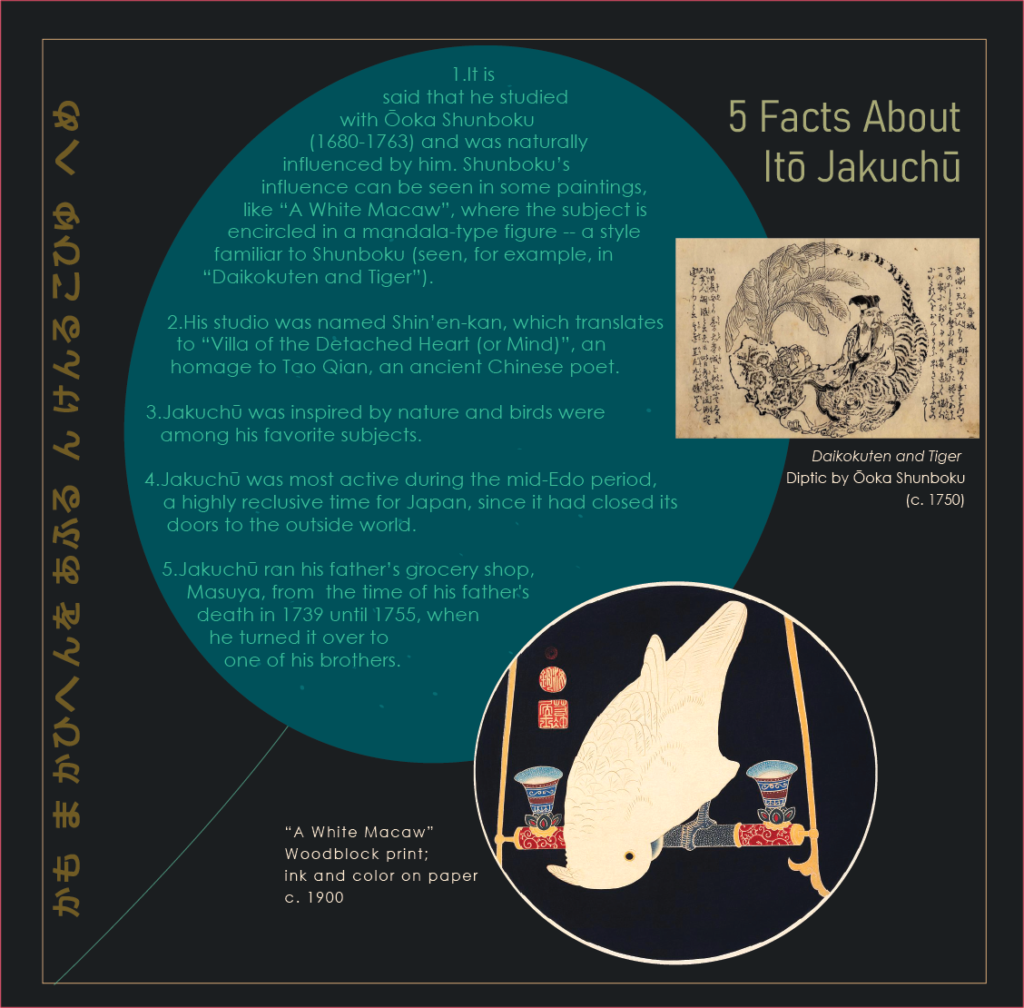

Some of that furyu-esque botanical elegance can be appreciated in Jakuchu’s paintings, with their intricate use of detail and pattern. Jakuchu often employed pointillism in his artworks, and though the context of his art is different from the Western perspective, they do have an impressionistic quality to them, even though Impressionism emerged in the late 1800s!

In any case, Japan’s hermitism during the Edo Period would have echoed the principles of furyu, which has been defined by art historians as “the recluse’s sense of aesthetics” (see an academic paper by Qiu, 2000, that explains the topic of furyu thoroughly).

Elegance certainly seems to be the main descriptor for Jakuchu’s work. But there is also a transcendent depth to his art. From a Westerner’s perspective, the use of a dramatic dark background is reminiscent of tenebrismo, and achieves a similar effect. Themes of transient beauty and the ephemeral quality of nature are brought to the foreground for consideration. Jakuchu, who’s artistic surname means “like the void”, was considered a lay Zen brother by the Buddhist community. As such, an appreciation for the uniqueness of the present moment contrasted against the existential experience of nothingness (not necessarily as dreadful as it sounds) would be a theme in line with Buddhist thinking.

Simply put, themes of life against death and activity against stillness seem to be at play in Jakuchu’s art. An interplay of color and starkness, darkness and motion situate the viewer in the scene captured by Jakuchu’s eye. Forms are outlined in such a way as to create a charged essence that pops into awareness. In this way, Jakuchu urges the viewer to appreciate the present moment with an artful, engaged eye.

Inspired by Jakuchu’s art, I created a PDF! Download a highly visual, 8-page article about Ito Jakuchu, with artful analysis of 3 of his artworks: The Paroquet, Parrot on the Branch of a Flowering Rose Bush, and Golden Pheasant in the Snow. Remarkably, all three artworks were frequently reproduced as woodblock prints in the 1900s, a century after Jakuchu’s death, after Japan transitioned from its Edo Period to the Meiji Era.

You can find the PDF at ko-fi.com/inkbrushmood (specifically here).

(It’s only $1! ^_^)

Leave a Reply